Hibiki Message

Employee Motivation and Stock Options (summarized translation)

|

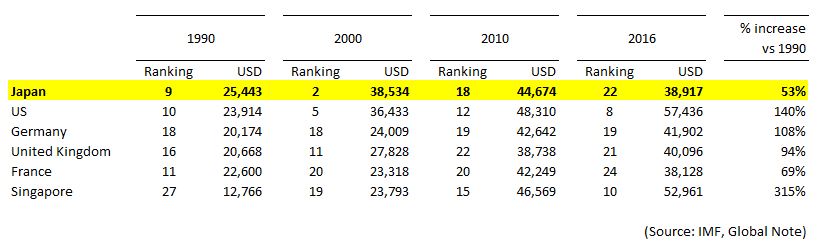

Lately, I’ve been thinking about stock compensation (restricted stock and stock options). I have always been a big fan of stock compensation, and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry recently came out in favor of restricted stock. Because of this endorsement from on high, some companies have been paying high fees to consultants and trust banks for advice on introducing options and other stock compensation with any real understanding or discussion of these instruments. Japanese people and companies have a tendency to follow fads, and this is the case with the current trend, which is spreading like wildfire. At least it’s good that they are moving toward adopting and expanding stock compensation, but I would just like to point out that the situation risks being one of plowing the field but forgetting the seeds. If stock prices were to fall, people could draw the mistaken conclusion that paying stock compensation was meaningless after all. These days, What I feel strongly is that the significance of having employees own company shares in the form of options or ESOP amounts to much more than the monetary value of the stock. It is an important corporate strategy that is key to motivation management and human resources training. Of course, the monetary aspect is very important in that it gives each employee a financial incentive, but my periodic discussions with corporate executives have given me the feeling that even the management team themselves sometimes do not fully understand the reason for granting shares to their fellow comrades. Underlying this is the attitude of “let us have specialists handle these difficult matters”. Some executives apparently lack confidence, and say that “managers are the experts at running the business, not looking after financial matters for their employees” which sounds like an excuse to me. Personally, I view the thorny problems that have plagued Japan’s corporate world as an overreaction to the excesses of the 1990s bubble economy (followed by the more recent credit crisis as well!), when companies and individuals alike jumped on the bandwagon. This defensive attitude by itself is not a problem, but in times of dramatic changes and ever increasing global competition, the damage from doing nothing, over the long run, could potentially destroy a company’s well-being. Let us go into details. This is a broad topic, so I would like to sort through it a bit as I proceed. Also, stock options actually have some technical and practical aspects. I will limit my discussion here to employee stock options (call options), in order to avoid the essence to be lost in translation. Let’s start with understanding current perceptions… According to the Tokyo Stock Exchange, 62.5% of listed companies had introduced some sort of incentive schemes as of March 2017, and 34.1% had inaugurated stock options programs. So what is going on with the remaining 66%? My hunch is that more senior people have sour memories of the huge unrealized losses from their ESOP programs after the bubble burst, and has some stigma towards anything related to ‘stocks’, resulting in emotional feeling that stock options are “something that relies on pathetic and greedy aspect of human being”. Back then ESOP programs were much more prevalent that stock options programs, and few would say that the situation wasn’t ugly. So, let’s sort through the “pathetic and greedy” aspects. Technically, a stock option is a mechanism whereby employees are granted options to purchase company stock during a certain period in the future if the share price is at or above a level determined by the issuing company. At that time, employees can exercise their right to purchase the share at this exercise price, and the employees will benefit from the difference between the market price and the exercise price. Naturally, since the employees benefit directly from the increase in the share price, their gut (drive, motivation) is stimulated, so they will work as hard as they can in the expectation that their company’s share price will rise. However, a company is a going concern. If the company’s past, present and future are categorized in this manner, three-to-six years is literally an instant, so some raise a logic that introducing this type of “short-term” incentive is meaningless. Also, some executives seem to disapprove of a mismatch between work and compensation, whereby individuals’ gains are determined by overall market factors (external factors) or factors other than their personal contributions. Anyway, I believe that such logic is extremely spurious. However, rather than explain why, I would like to make a brief detour. It is easy to say other people are wrong, but such antagonistic approach will never be constructive. The core essence of overall Japanese corporate organization, the Japanese work style, the system of promotion, compensation and other systems, and so-called performance assessments originated in the rapid economic growth period of the 1970s, when I was a mere child and my father was a hard-working white-collar worker at a fast growing company. How is today different from back then? The 1970s were clearly an overall growth period. It was a time when everyone in Japan had great future expectations. Japan’ underwent an amazing technological revolution, and the country benefited from its large and growing population. The harder we worked, the more our companies expanded and our salaries rose. But that is not the case these days. Growth is stagnant, the myth of lifelong employment at large corporations is being dismantled, the population is rapidly aging due to the low birthrate, tax rates are going up, and social welfare costs are skyrocketing. The more objectively we look at these trends, the more it seems that each person needs to take steps to protect themselves. Therefore, society, people, and companies need to change. The table below compares per-capita nominal gross domestic product (GDP), which is a metric for a country’s value-added, for Japan and other major nations. Japan’s per-capita nominal GDP has risen by more than 50% since 1990, but its ranking among the other countries has dropped remarkably. This means that, while each citizen has become somewhat more affluent in absolute terms, they have become poorer in relative terms. Meanwhile, two contradictory tectonic shifts are taking place with respect to the concept of human resources. One (and this is particularly the case for Japan) is the scarcity of workers as a result of population aging and the low birthrate. In workplace competition, the winners get promoted, while the rest are taken care of until retirement, as they made do with the age-based pay structure since they were young. This set-up functions normally when a business is expanding and number of titles are growing. However, when titled positions are shrinking due to fiercer competition, lower profit margins, governance issues, and bad business decisions, the costs of maintaining such a system pile up, and, of course, no promotion or no pay rise means declining worker morale condition. Human resources are precious, and the effective use of their drive and motivation, is fundamentally necessary to the maintenance and expansion of a company’s comparative advantage. The other tectonic shift is obviously the “digitization of relatively low value-added labor” through the advance of information technology (IT) geared toward artificial intelligence (AI). From their huge daily work flows, companies are keenly aware that they need to determine how to allocate their resources–what to digitize, what to outsource, when to rely on employees’ intellectual work–so that they can maintain a comparative advantage over the long term. Of course, this type of thing has no precedent, so it would be perilous to make value judgments that rely on past experience. In the past, Japanese companies’ human resources programs have been characterized by (1) age-based pay systems, which underpay younger employees for their value-added and overpay older employees for their past accomplishments, (2) employee performance reviews based on assessment of and commendation for mastering the company’s introvertedly tailor-made longstanding practices, and (3) the lifetime employment system, which educates employees with the company’s proprietary technology and way of doing business, thus reducing people’s job mobility and forcing employees to cultivate a sense of belonging. This approach has many favorable attributes, of course, but it also increases the risk of the “Galapagos syndrome” by reducing creativity and nurturing only in-house value criteria. No matter how much the management teams leading these companies shift their perceptions, the essence of the organization will not change as long as these valuation criteria and assessment methods remain in place. Speaking of individuals, at a time when their pay is not going up, the number of positions at their companies is going down, and even the lifetime employment system, which had been a tacit understanding, is becoming precarious, we hear that people’s trust in their companies is increasingly eroding, those who are savvy are protecting themselves by getting involved in more outside activities, such as acquiring qualifications and other credentials, and applicants to company ESOP programs are down compared to the past. Behind this is the fact that nowadays social networks and the like have made it possible for people to be constantly connected with others so that they can and do enjoy life without devoting themselves to social interaction with people at work. In other words, for corporate executives, this is an age in which it is necessary to use more sophisticated techniques than ever to win people over, techniques that will develop business over the long term while bringing together people who have no illusions about lifetime employment, little sense of belonging, and diverse value systems and outlooks on life. So, what is the key? I think it is simply the shared experience of “success”. This could entail diverse and wide-ranging things, from such little things as being congratulated by colleagues after one’s small accomplishments are written up in the company news flyer to such major events as the acquisition of new customers, a new venture business developed by an employee being upgraded to formal department status, the company’s overseas expansion, or even its listing on the stock exchange or new partnership agreements. Accumulating these types of exciting “shared success stories” is linked with “a bright future for each individual.” It should bring together people who were tending toward self-preservation, and it should induce a shift to an attitude of wanting to foster the preservation of the organization, which consists of one’s colleagues. This power of this empathy will naturally strengthen the organization’s survival instinct. The key is to figure out how to imbue employees with a sense of being personally content to put forward their best efforts for the company (their colleagues) in order to accumulate assets. The era of rapid economic growth when sales were on an upward trajectory generated many success stories, but this myth was destroyed with the collapse of the bubble economy, and there have been some tragic cases in which people who belonged to their company’s shareholders’ club have lost both their jobs and their assets. Except at start-ups, it’s very rare these days to have a strong experience of shared success that really unites the organization and individuals. Once an executive told me, “When we granted shares to all the employees when we listed publicly, solidarity increased because the employees were devastatingly impressed by the creation of value that came from the act of listing our shares. For example, former female employees who had resigned due to wanting to raise her new baby full-time, returned to the company on a part-time basis after such child has become teenager, even at low pay.” This was a wonderful shared success story that brought emotional ties between people. Therefore, it is my opinion that stock options are a particularly effective means of sharing success(1). Such a program embodies an understanding that compensation impacts motivation more than just financially. It is difficult to get the entire employee base to understand this program properly and to influence their behavior and thought patterns. The company may not obtain the desired results unless it can instill this understanding by taking the trouble to hold internal seminars and the like. However, the atmosphere within the company will definitely be transformed if the company can create a cycle like that shown in the figure below, even if it takes time. The results, whereby employees receive not only their salaries and bonuses but are given the right to become owners of the companies to which they belong, are so great that they cannot be overstated. The experience of employees’ personal assets growing in this way will develop into a “thought pattern” through repeated experience, although some may dismiss it as a one-time phenomenon, or “simple luck.” Another function of stock options is that the company is able to control the time span of employees’ morale. Let’s assume, for instance, that your company has a medium-term plan that ends in three years. By having the options vest three to five years from now, the company can induce employees to channel their efforts during this period. Also, the outflow of key employees due to job changes inflicts serious damage at a time when human resources are precious. However, under Japanese companies’ current compensation systems, it is difficult to implement much in the way of pay differentials among associates, and increasing compensation before achieving results could potentially turn the relevant employees into free riders and have a negative impact on morale. Granting stock options plays an important role as a means of retaining those employees who would be the leaders of the coming generation. The outflow of technical experts to overseas corporations from large Japanese electronics makers and other companies that have fallen on hard times has become conspicuous over the past several years. If managerial errors interfere with employees’ desires for a “bright future” of motivation and asset formation, the best employees will be the first to leave. Having motivated employees is essential to prevent this from happening, and options are a powerful motivating “spice.” Companies are going concerns with long time horizons, but human life is finite. Furthermore, employees’ working lives usually span 40 years. With this in mind, if we were to, say, award stock options every four years to employees with a certain period of service as a part of their performance review, these periods would be equivalent to 10% of their work lives, and companies could use such a system to augment employees’ goals on a periodic basis. For an individual employee, a 10% segment of one’s work life is not a short time span by any means. Such a time span to a certain extent matches employees’ satisfaction with their asset formation, so they can be re-motivated and their sense of belonging will continue to grow. If this shed light on the basic truth that corporate energy (that builds its going concern status) is heavily influenced by people’s perceptions and how they spend their lives, which are finite, I think that the cost-benefit of granting stock options to employees is immeasurable outside from the standpoint of simple financial gain. As I stated previously, nowadays both companies and individuals alike are navigating through much anxiety about Japan’s future. This is why people are saving their money and feeling that they need to protect themselves (another reason is that they don’t have any fear of inflation). However, it is encouraging that in an environment of extremely low interest rates, the promotion of governance codes and managing for profit (return on equity) is leading most companies to take more proactive business and financial strategies with respect to capital expenditures, mergers and acquisitions, dividends, share buybacks, and so on. As these changes take place, because this is purely an internal situation, the task of incorporating such useful instruments as options into a reform of the performance review system and its criteria will be not to involve precedent or psychological spells, as it is easy to do. By tackling the issue this way, I think we will finally achieve the true “work style reform” that has recently been the topic of discussion. In conclusion, I heartily commend those executives and corporate planning departments who are giving objective consideration to implementing stock options as one of the various programs for preemptively generating more value-added from work and making employees feel glad that they are working at their company. Recently, company outings have suddenly become a hot topic in motivational management in Japan, so many companies have started to resurrect them or implement them for the first time ever. This may be strange, but aren’t stock options and company trips actually ways of accomplishing the same goal? When we think about it this way, a stock option, which seems somewhat inanimate, starts looking very human indeed. It is a hot and rainy summer, but I hope you all have a nice one! (1) Under Japan’s current tax system, individuals who hold options incur a tax liability (are subject to taxation) when they exercise those options, so in most cases, those who do not have adequate savings have to sell the shares in the market after acquiring them through an option exercise. Unfortunately, issuing options does not increase the number of insider shareholders or stabilize the shareholder base over the long term. |

Chief Investment Officer

Hibiki Path Advisors Pte. Ltd.

Yuya Shimizu